Haiti Journal: Part I

March 13On flight from Miami to Port-au-Prince. Isle seat, 13C. Total flying time just under 2 hours. I am traveling with my wife's cousin Ricky, his wife Shae, two or their children, 6 and 4, and their nephew, 14. We are en route to the Canaan Christian Community, an orphanage and school, in Montrouis, Haiti, to volunteer for a week.I fall asleep during take off, then wake and write for an hour. After closing my laptop, I read a few more pages of Tracey Kidder’s Mountains Beyond Mountains, a book on Dr. Paul Farmer, a man who has devoted most of his life to providing medical care in Haiti.No one is seated next to me, so I move to the window seat as the coastline of Haiti comes into view. Outside are mountains, mostly barren, stripped of forestation. No trees equals less rain equals longer droughts and the hills and mountains of Haiti show it. This is arid, scorched earth.Flying over the city of Port-au-Prince, I see makeshift homes, industrial buildings, dwellings that have been destroyed by natural disasters and never repaired. Trash litters the hillsides. Thousands of people crowd the streets, hundreds gather in a dried riverbed. Before I even land it’s clear the desperate conditions in which many Haitians live.

A Brief History of Haiti

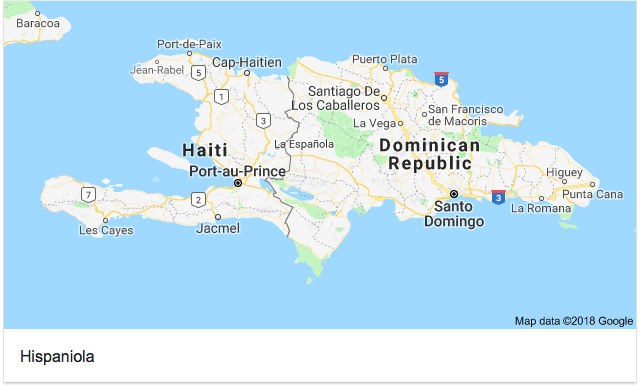

The Taino are the native people of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic). Their creation story tells of how their people originated from the caves of Hispaniola’s sacred mountains. In the decades following Christopher Columbus’ arrival in 1492, the Taino were nearly wiped out by the Spanish. During the 17thcentury France staked its claim to the western third of the island. Utilizing the labor of several hundred thousand African slaves, the French established sizable forestry and sugar cane operations, turning this territory into one of the richest in the Caribbean.A slave revolt began in 1791 and was led by Toussaint L’Ouverture, a leader well versed in stoic philosophy and the writings of Machiavelli. L’Ouverture is quoted as saying, “I was born a slave, but nature gave me the soul of a free man.” Despite Napoleon Bonaparte’s efforts to squash the revolution, Haiti won independence from the French in 1804. From that time, Haiti has been marred by political corruption, environmental plunder, and catastrophic natural disasters.

During the 17thcentury France staked its claim to the western third of the island. Utilizing the labor of several hundred thousand African slaves, the French established sizable forestry and sugar cane operations, turning this territory into one of the richest in the Caribbean.A slave revolt began in 1791 and was led by Toussaint L’Ouverture, a leader well versed in stoic philosophy and the writings of Machiavelli. L’Ouverture is quoted as saying, “I was born a slave, but nature gave me the soul of a free man.” Despite Napoleon Bonaparte’s efforts to squash the revolution, Haiti won independence from the French in 1804. From that time, Haiti has been marred by political corruption, environmental plunder, and catastrophic natural disasters.

Arrival in Port-au-Prince

We pick up our luggage. Pastor Henri and Sister Gladys, the couple that runs the orphanage, walk us right through customs without a problem. This is unusual. Ricky explains that when you arrive without the Pastor, who has obvious connections, security conducts a thorough search of your luggage. Once they have removed everything from your bags and are satisfied, they leave a mess for you to repack. As we walk through the doors, I feel lucky to have bypassed such a situation.Outside the heat is heavy and I notice the smell of burning tires. Burning tires, I have read, can be an indication of a demonstration, a large group of people angry about something and protesting in the streets. Prior to leaving, I registered with the U.S. Embassy in Port-au-Prince and the State Departments Safe Traveler Program. Since then I received numerous email warnings informing me of demonstrations and areas of the city that should be avoided. I check my phone, but my emails will not download. I wonder what might be happening and grow concerned we may get tangled up in a some kind of situation as we leave the city.We drag our bags to the parking lot, where a pickup truck and a crimson colored minivan await our arrival. Josh, Sister Glady’s son, is also there to greet us. He was born in Haiti, but has lived all over — Ft. Lauderdale, California, and Corvallis, Oregon. Now he works at the orphanage in Montrouis.All of our luggage is tossed into the back of the pickup and strapped down. We all pile into the minivan, which, I am grateful, has air condition. Pastor Henri tells us it was donated by the parent’s of a Canaan teacher who is from Canada. It took four months for them to get the minivan out of customs, and when they finally did, all of the van's tools had been stolen.I help Sister Gladys into the minivan, as her knee gives her problems. Josh drives the pick up, our luggage secure, but fully exposed. Ricky tells me he usually rides to the orphanage in the back of the pickup. It’s an hour and a half drive. This is hard to fathom. Even harder once we begin to navigate the dangerous streets of Port-au-Prince. Again, I am grateful for the closed-off mini-van and its air condition. I notice several remodeled pickup trucks and vans with people hanging off the sides. These are called “Tap-Taps” and are used for public transportation. People “tap-tap” if they want to get off, which is where the name comes from. They are all colorfully painted with murals and portraits of iconic figures – I see one with Bob Marley, another with Tupac – and converted to carry as many as 15 people, though not safely. There is a driver and a man in the back who collects the fee. Without a fee collector, many people would jump off without paying. Every Tap-Tap I see is filled to capacity. People, I have noticed, ride on the tops of buses, as well. Not very safe, obviously, but even less so in Haiti given all the low hanging power lines.Many of the buildings and houses of Port-au-Prince are still in ruins from the 2010 earthquake that killed an estimated 300,000 and left 1.5 million homeless. There are also a large number of structures that appear to have been abandoned early in the building phase. These structures consist of cinderblocks stacked three or four feet high and rebar sticking out the top. Many seem to be occupied anyway. The unfinished structures where people have taken up residence are made slightly more whole with scraps of material. All of these dwellings are without plumbing, open to the elements, some with improvised doors, gates, or plastic tarps to create some sort of barrier.Trash litters the landscape of Port-au-Prince. The streets, gutters, and hillsides are all covered, as if it fell from the sky in a recent storm. Vendors line the main thoroughfares of the city. Most appear to be selling similar goods. There are thousands of people everywhere. Hundreds of mopeds and motorcycles navigating the streets. Whatever traffic laws have been written are disregarded. The way people drive reminds me of Cairo. A cacophony of horns.Throngs of people walk along the side of the roads, as cars race past at high speeds. There are women balancing large baskets and buckets on their heads without the use of hands. Small children, alone, casually watching cars whizz by from an unsafe distance. All of these people seem to be one misstep away from of being run over.

I notice several remodeled pickup trucks and vans with people hanging off the sides. These are called “Tap-Taps” and are used for public transportation. People “tap-tap” if they want to get off, which is where the name comes from. They are all colorfully painted with murals and portraits of iconic figures – I see one with Bob Marley, another with Tupac – and converted to carry as many as 15 people, though not safely. There is a driver and a man in the back who collects the fee. Without a fee collector, many people would jump off without paying. Every Tap-Tap I see is filled to capacity. People, I have noticed, ride on the tops of buses, as well. Not very safe, obviously, but even less so in Haiti given all the low hanging power lines.Many of the buildings and houses of Port-au-Prince are still in ruins from the 2010 earthquake that killed an estimated 300,000 and left 1.5 million homeless. There are also a large number of structures that appear to have been abandoned early in the building phase. These structures consist of cinderblocks stacked three or four feet high and rebar sticking out the top. Many seem to be occupied anyway. The unfinished structures where people have taken up residence are made slightly more whole with scraps of material. All of these dwellings are without plumbing, open to the elements, some with improvised doors, gates, or plastic tarps to create some sort of barrier.Trash litters the landscape of Port-au-Prince. The streets, gutters, and hillsides are all covered, as if it fell from the sky in a recent storm. Vendors line the main thoroughfares of the city. Most appear to be selling similar goods. There are thousands of people everywhere. Hundreds of mopeds and motorcycles navigating the streets. Whatever traffic laws have been written are disregarded. The way people drive reminds me of Cairo. A cacophony of horns.Throngs of people walk along the side of the roads, as cars race past at high speeds. There are women balancing large baskets and buckets on their heads without the use of hands. Small children, alone, casually watching cars whizz by from an unsafe distance. All of these people seem to be one misstep away from of being run over.

Armed Guards and Groceries

We pull into the parking lot of a grocery store. It is guarded by at least five men with shotguns hanging off their shoulders. We step out of the van to the sights, sounds, and smells of a chaotic city. It’s sensory overload for a first time visitor. The people and traffic. The shouting and honking and men with guns, their fingers resting on the triggers – a scene in which it is hard to pinpoint any semblance of order.Inside the grocery store I look around at shelves stocked top to bottom with an assortment of goods. Canned goods, sauces, pasta, rice, cereals, breads. Refrigerated sections with meats, steaks, fish, chicken, sodas. Another station with hot pizza and fried chicken. Every shelf is full, top to bottom, with many of the brands I see back in the U.S. To find myself browsing a well-funded, well-managed grocery store comes as a surprise, to be honest, given the conditions of the surrounding area.I stroll the isles as Pastor Henri and Sister Gladys fill their carts. Ricky mentions that he’s been told to keep his passport with him at all times. When I ask why, he says, “In case we ever have to take off running.” This is alarming. In Haiti, it seems visitors need to be prepared for anything. There could be a robbery, a riot or an earthquake. “I left my passport in the van,” I tell him. “Should I go get it?” He tells me we won’t be there much longer and that we should be fine. For the remainder of the shopping experience, I feel vulnerable without my passport. I also make a mental note to be hyper-aware of my surroundings.Inside the store there are lots of people just standing around, loitering, with no intention of shopping. Every one of them watches us shop with gazes that are impossible to interpret. I wonder if they are in the store for no other reason than to enjoy the air conditioning. If they are, I don’t blame them.Pastor Henri and Sister Gladys fill two carts. Beef, steaks, chicken, potatoes, bread, peanut butter and jelly, pancake mix, eggs, pasta and sauce, drinks, candy. I go and check on the van. A man with a shotgun stands a few feet away. I walk back into the store, grab a coke from the cooler and Pastor Henri pays for it while he is checking out. We load everything into the back of the mini-van and climb inside. Before Pastor Henri starts the van, he says a prayer, thanking God for our food, for the blessing of guests, and for our safe drive to Canaan. I open the Coke and take a sip. It is cold and sweet. More than just a coke, it seems an indulgence.Night falls over Port-au-Prince. Moving back into the traffic and out of the city, I notice several vehicles driving without lights. No headlights, no taillights. I worry about this for a moment, then forget it, assuming that out of necessity those without lights have become adept at nighttime driving.There is both a comfort and an eeriness to taking your first drive through a new country at night. The darkness protects you from the reality that exists outside and shields your presence from others. Yet it also works in reverse, deepening my anxiety over all the unknowns.

A Tragic Accident

Twenty minutes into our drive we stop at a gas station to fill up and use the bathroom. A man with a shotgun guards the station. Another man sits in a chair, guarding the bathroom. I get out of the van, stretch, notice the smell of smoke in the air. It isn’t tires this time though. This smoke smells like a campfire. It’s wood. I wonder about the average life expectancy of a Haitian given the high rate of diseases, the recurring natural disasters, the constant smoke in the air, and make a note to look it up. A vintage school bus pulls into the gas station, painted green, the inside packed, with a dozen more people riding on top. Across from the gas station a building is under construction and nearly complete. It is two-stories, painted yellow with white pillars. Possibly a hotel, or an office building.We leave the gas station continue down a two-lane interstate, driving 50-60 mph. A few minutes into the drive, I am looking out the window in somewhat of a trance when I see an explosion of glass and metal. Right beside us, in the oncoming lane, the hood of a pickup folds like an accordion into the back of an abandoned dump truck. The pickup’s airbag deploys. I look back as we pass and see dirt and gravel pouring from the dump truck onto the pickup’s smashed windshield. Pastor Henri pulls the minivan to the side of the road and stops. I certain we just witnessed a fatality.The Pastor opens his door and jogs toward the pickup. Ricky tells me to follow. We jump out, look around to make sure the traffic has stopped, and run down the street to the man in the truck. The driver is conscious, but groggy. Headlights of stopped cars provide enough light to see. Shae comes to check on the man, as well. The Pastor talks to him in Creole. More people gather. There is yelling. People shouting things I can’t understand. Several men start pulling on the back of the pickup.Ricky and I run to help. I overlap my arms with another man’s arms as we tug at the back of the pickup. We are trying to tear it away from the dump truck, which is still pouring dirt and gravel over the top of the pickup's splintered windshield. Within a couple minutes, there are at least 20 people at the scene. Everyone is frantic. More people join us in the back, trying to tear the pickup away so that we can free the man from the wreckage. It's no use.From nowhere an old truck with a tow pulley makes its way through traffic and stops at the crash. The driver lowers a pulley off the front of the van and latches it to the back fender of the pickup. He then starts the pulley crank and puts his truck in reverse. The back of the pickup is lifted off the ground. The fender starts to bend. The tires of the tow truck are spinning. Smoke fills the air.I turn and run, yelling for Ricky and Shae to do the same, worried that the fender is going to slingshot into the crowd and kill someone. I turn back just as the hook slips loose and snaps backward, nearly hitting several people. Everyone is yelling and running around. Undeterred, the man again hooks the pulley to the fender and tries again. Again the pickup is lifted off the ground. It’s the same scene — squealing tires, smoke, the fender bending even more — but this time the strap snaps and the pickup drops hard to the ground.Shae is distraught, worried that the driver will die before we can free him from the pickup. I run back to the minivan and explain to Sister Gladys what is happening. Jogging back to the scene I meet up with Ricky, Shae and the Pastor. There are now 40 or 50 people standing around. More people yelling in Creole. The scene is chaotic. A minute later, a flatbed truck of police arrive. They are dressed in military uniform. Where did they come from?Finally, the Pastor says, “There’s nothing more we can do. They are going to have to cut him out somehow. Let’s go.”As we drive away from the accident, I say a prayer for the driver, feeling somewhat empty and helpless given the things I have witnessed within an hour of our arrival.